Trauma Is An Experience, Not An Event

It seems like "trauma" has become one of those household terms everyone talks about. I took a look at the number of average monthly Google searches for "trauma" in the U.S., and found that it has grown over 20% in only one year (this article was written in 2018). As with other terms that became mainstream (for instance "addiction" or "narcissism"), I suspect the price of increased awareness is a diluted understanding of what they really mean.

After hearing my patients talk about their experiences, reflecting on my own upbringing, and studying some of the literature on trauma, I believe the following can be a useful working definition:

Trauma is an experience that overwhelms our capacity to regulate our emotions and results in fragmentation and dissociation.

While this may not be a comprehensive or final definition, I think it captures a few ideas that are important:

Trauma impairs our capacity to regulate our emotions. We feel worried, irritated, anxious, or afraid, consciously or not, and we cannot self-soothe or seek support from others.

Trauma creates fragmentation and dissociation. Whether we understand this as an unconscious defense mechanism (e.g., splitting, projection or repression) or as a neurological issue (e.g., thalamus gone offline, hypersensitive amygdala), dissociation is a key trait of trauma.

However, in this post I want to expand on the idea that trauma is not about a past event, but about a present experience.

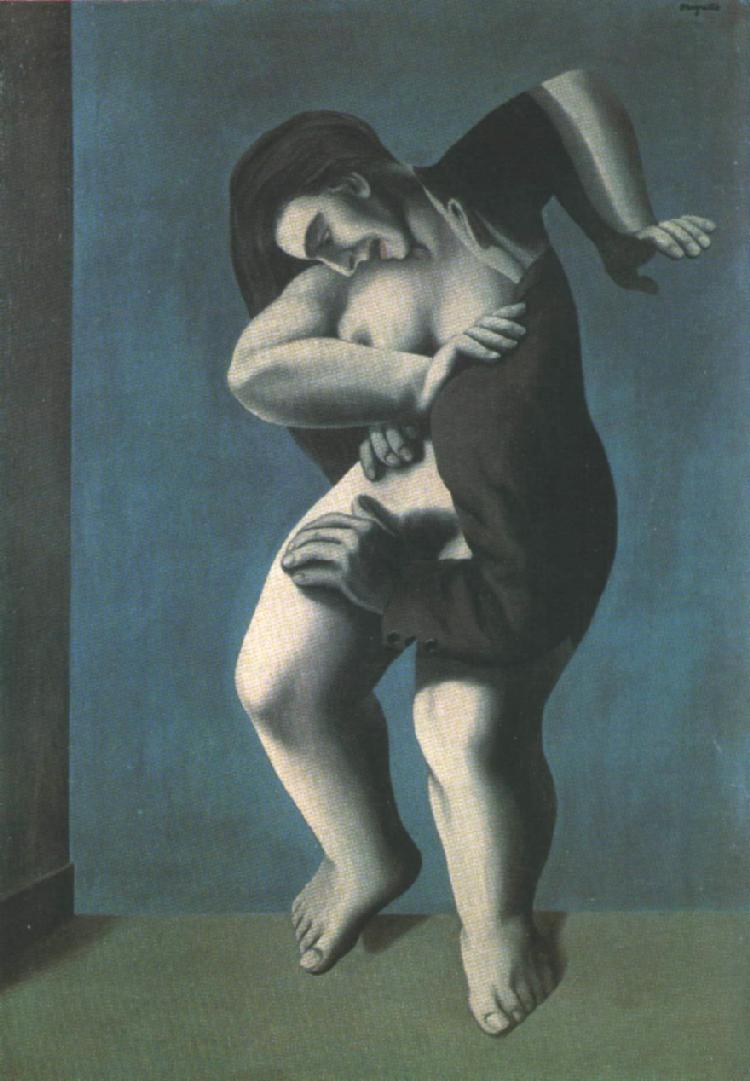

I think the idea of trauma as a present experience is captured dramatically and beautifully in a 1930 painting by Belgian artist René Magritte.

The Titanic Days

I liked Magritte since I was a boy, but I saw "The Titanic Days" (Les jours gigantesques)for the first time a couple of years ago, at a special exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Rene Magritte - The Titanic Days (1930)

I was stunned by the power and the violence of this piece. What I see is not a rape attempt happening now, but how a past experience is stored in the woman's body and felt in the present moment. I see the terror of her frozen expression, reminiscent of the so-called "thousand-yard stare," the tension of her entire body and the desperate attempt to push back an attacker from a real or imagined past. I notice the stark contrast of colors in the woman's body and I see the traumatic struggle between life and death, and the need to keep part of her in the shadows. No words are required to convey the drama, and no words could probably do justice to the horror; trauma, in fact, impairs our capacity to develop a cohesive narrative. The experience is overwhelming and occupies most of the space on the canvas, yet the atmosphere feels completely desolate: we know nobody will come to her help. Is the blue background a wall, keeping this woman cornered against the attacker living in her body and in her mind, or does it suggest an abyss, making the woman one step away from oblivion?

We can only imagine the details of what actually happened in this woman's past. Was she sexually abused as an adult by a coworker? Was she touched in uncomfortable ways as a young girl by a family friend? Was she somehow sexualized when she was a toddler by her father? How much of what happened was real and how much a creation of her mind?

These are important questions to consider, but not as important as the terror, the isolation, and the helplessness she is experiencing in the present moment. When I stand in front of this painting, much like when I sit across from my patients in therapy, what I see is this woman's suffering in the here and now. I don't need to know all the actual details of her story, but I am curious about the meaning she assigned to it, about how it feels in her body, her mind and her spirit, and about the ways it might be getting in the way of being her full self.

Trauma is like a splinter

I remembered Magritte's painting some months ago, when I read Bessel van der Kolk, a leading trauma researcher, suggesting the metaphor of trauma as a splinter: it is the body’s response to the foreign object that becomes the problem, more than the object itself.

This idea has been around for some time. Twenty years ago Peter Lavine, developer of the somatic experiencing approach for trauma treatment, wrote:

"Traumatic symptoms are not caused by the triggering event itself. They stem from the frozen residue of energy that has not been resolved and discharged; this residue remains trapped in the nervous system where it can wreak havoc on our bodies and spirits."

It is worth noting that this notion is even older. Not to make the point that everything goes back to Freud, but over a hundred years earlier he and his colleague Josef Breuer advanced a similar idea in "Studies on Hysteria":

"Psychical trauma – or more precisely the memory of the trauma – acts like a foreign body which long after its entry must continue to be regarded as the agent that still is at work."

I think there is value in talking about "traumatic events," but I believe that it is critical to shift our focus toward the ways in which trauma stays with us. Trauma is not remembered, but reenacted. It is not about something that happened in the past, but about its consequences in the present, about the conscious or unconscious meaning we give to our experience, and how that experience defines how it feels to be in our body and in our mind.

It doesn't take a big event

The notion of trauma as an experience is valid for traditional PTSD trauma (e.g., when there is a specific event or situation that triggers the traumatic experience, such as sexual abuse, a war or a natural disaster), and for complex developmental trauma, which is more insidious.

Complex trauma is characterized by an upbringing defined by patterns of inconsistency, neglect or abuse. Emotions are not expressed, not allowed, or even punished. A specific "big" event is not necessary; repeated and chronic interpersonal wounds can overwhelm the child's capacity to regulate emotions, and create fragmentation and dissociation.

Most people I have seen in therapy have experienced some form of developmental trauma. They felt unseen and unheard by physically or emotionally absent parents. They did not feel taken care of, taken seriously, or taken into account. They believed their needs were not important or would ever be met. They had to carry within, in silence, destructive family secrets. They had to be parents to their parents from a very early age. They needed to constantly perform, or pretend to be someone else, in order to feel accepted or loved. They had to learn to soothe themselves. They lived feeling that nothing they did would ever be enough.

All these experiences from the past are reenacted and experienced in the present, keeping them from feeling safe, loved, worthy, and trusting in others or themselves. They get in the way of becoming self-aware, of letting go of control, of developing vulnerable and intimate relationships. They make them feel either in high alert or depleted. These experiences keep them from being fully alive.

From traumatic experience to healing experience

The most important thing therapists can do to work through traumatic experiences of this kind is to offer the opportunity for a healing experience.

The essence of that healing experience is not a matter of technique, approach or theory, and goes beyond the promise of providing a safe, calm and reliable environment. I believe the question is about love, authenticity and curiosity.

For me, the question is about being self-aware and curious about my own reactions, about how I think of, feel with, and relate to the person in front of me. It is about being a human being first and a psychotherapist second, which is a difficult task. Often times I get caught up in the need to make sure that I am saying the right words, giving the best feedback, offering the most insightful interpretation, or providing a useful perspective. Instead, I can trust that my presence, my curiosity, my compassion and my humanity, with its flaws and imperfections, is the first thing that matters.

Do my patients feel heard and seen by me? Would they tell me if they didn't? Do they feel there is room for their feelings toward me, whether they come from a place of anger, hurt, sadness, joy, love or desire? Can they express them trusting that our relationship will survive? Can they count on me, and trust that I will provide safe boundaries? Can they feel that every part of themselves is acknowledged, accepted and valued?

I believe these are the types of questions that define a healing therapeutic experience. They matter not only because they allow patients to recognize current dysfunctional relationship patterns in their lives, but mainly because they have the potential to provide an experience that was not available to them when they were growing up. We cannot change the past, but we can help our patients change the relationship they have with it, by offering them the opportunity to experience and develop self-awareness, acceptance, and unconditional love.

If you have a question or would like to schedule an appointment to work on trauma, childhood trauma, or complex trauma with one of our Chicago therapists, please contact us today.